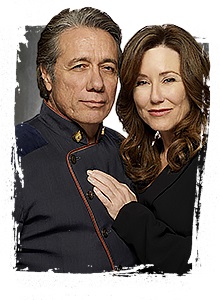

Prime Time: Never The Ingenue, Mary Mcdonnell Gives Dark Side A Different Wrinkle

Nancy Mills

August 13, 1995

LOS ANGELES — “As a culture, we’re afraid of women who don’t behave properly,” says actress Mary McDonnell. “I find that a trap as a woman, and it’s certainly a trap as an artist because you don’t really get full expression.”

McDonnell, who came to prominence with her Oscar-nominated performance in “Dances with Wolves,” is not afraid to misbehave on camera. Her character, Stands With a Fist, a white woman raised by Indians, followed her own unconventional muse. And as a paraplegic ex-soap opera actress in “Passion Fish,” another Oscar-nominated performance, McDonnell played an uncompromising, bitter drunk.

“Don’t get me wrong,” McDonnell says. “Playing unsympathetic women does scare me. It’s not like I say, `Oh, good, give me her.’ But it’s a wonderful opportunity to release my own darker nature. Also, women and men need to see their potential darkness reflected to them so they understand more about it. Doing that excites me.”

Standing under a tree at the Stewart Studioplex in Valencia, 30 miles north of Los Angeles, McDonnell could be the woman next door. With her glossy, long brown hair glinting red in the sun, she radiates wholesomeness.

She has some pronounced wrinkles around her eyes, natural at 42. She doesn’t try to hide them, nor does she imagine she’ll resort to plastic surgery. Why should she when Kevin Costner says he cast her in “Dances with Wolves,” because he wanted “someone with a few lines on her face?”

Since then, older women have been heartened to see McDonnell, rather than some 20-year-old, opposite such actors as Nick Nolte (“Blue Chips”), Robert Redford (“Sneakers”) and Kevin Kline (“Grand Canyon”).

In “Red Rain,” a Showtime movie to air later this year, she plays the troubled wife of Randy Quaid. When he is found dead in the burned-out wreck of her car, she is tried for his murder.

“She’s an example of women who haven’t found ways of dealing with problems that emerge in their marriage,” McDonnell says.

“I believe there are a lot of women like her out there, but we don’t know much about them.

“They are upsetting to us as a culture. We don’t want our women to behave this way. We want them to rise above their unhappiness in their marriage, rise above the abuse, rise above their husband’s affairs. We’re so busy protecting our idea of what marriage needs to be, what a wife needs to be, that we’re not really looking at what marriage is.”

McDonnell, who has been married to actor Randle Mell for 11 years, has made a study of the subject.

“Marriage is a lot of hard work,” she says. “It’s enormously fulfilling, but it requires tremendous attention. We’re really lucky because it’s very, very difficult these days to keep a marriage and a family together.”

She and Mell have two young children, Olivia, 7, and Michael, turning 1 year old this month.

“My heart goes out to people when it doesn’t happen, and when people are holding it together I’m in awe,” McDonnell says. “It was very different for our parents, but our generation has all this new information and role changes. Marriage has had to go through an amazing forced growth, and it doesn’t always stand up to the growth.”

A product of ’70s feminism, McDonnell was too busy developing her career during her 20s to think much about commitment.

“We took a little bit longer to marry because the women ahead of us had earned us the opportunity to work at what we wanted to do,” she says. “It was OK to be a single woman with a lot going on.

“I was in New York for 10 years before I married, and my single life was very exciting. Not being attached really helped me focus on the work and carve out a place for myself. During those days–mid-’70s to mid-’80s–I knew very few women of any age who were married. The men were quite fine about it as well. The lack of definition was quite wonderful.”

Growing up in Ithaca, N.Y., where her father was a financial officer for Borg-Warner, McDonnell had no life plan.

“I was a cheerleader in high school. My family thought I was dramatic, but we never went to the theater and were much more interested in sports.

“Then when I was choosing courses for college , my father said, `Why not take Introduction to Theater?’ I did, and my brain came alive. I was on fire, learning everything quick.

“I had a lot of catching up to do–most of the other drama students had wanted to be actors since they were 3.

“I never even saw a play until I was in college and went to `A Little Night Music.’ The first play I did in college was Arthur Miller’s `The Crucible.’ I played one of the screaming women. The first night was one of the most exciting nights of my life.”

“It marked a transition for me as an actress,” she recalls. “The women in the company at that time happened to be very short and slight , so I ended up doing character roles rather than the roles I’d normally do. For instance, in Tom Stoppard’s `After Magritte,’ I played the grandmother. I was put in situations where I had to figure how to act. I probably learned more that year than I’d ever learned, as painful as it was.”

Afterward, McDonnell headed for New York to hunt for jobs in the theater. To support herself, she did everything from waitressing to working in a bagel store.

“The worst job I ever had was selling Fuller brushes in Rockefeller Center. I was terrible at it, and I ended up owing them money. I was talking too much. But then I lucked out and got in Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play `Buried Child,’ in 1978, and that’s when everyone noticed me.”

In 1981, McDonnell won an Obie Award for “Still Life.” Her work in regional theater led to playing a doctor on a 1984 CBS series, “E/R.” She moved into feature films with John Sayles’ “Matewan” in 1987, but Costner truly changed her life by casting her in “Dances With Wolves.”

“Kevin did a particularly wonderful thing that I’ll never forget,” McDonnell says. “When he was editing `Dances with Wolves,’ my mother was dying of cancer. He telephoned me at my sister’s house when my mother was in a very bad place to tell me how well the movie had been testing. He said, `How’s your mother? Is she going to make it to the opening?’

“This was July, and the movie was opening in October. I said, `Frankly, I don’t know.’ The next day he Fed-Exed a rough cut for me to play for her at the hospital.

“It was quite a risk for him to let go of the film because it was his baby, his pride and joy. I was really impressed with that, and I’ve never forgotten it.

“My mother got to see what the film was, and, in fact, she didn’t make it to the opening. Kevin is a very generous man.

“The men I’ve worked with have generally been decent human beings,” she says. “Robert Redford takes on a lot of responsibility in his life. With him there’s a certain clarity about getting the work done. Nick Nolte is fun. He’s a very dedicated actor who really works hard to stay inside the role he’s playing.”

Nevertheless, soon McDonnell may not be appearing opposite such illustrious gentlemen.

“I’ve progressed beyond playing the generic female,” she says. “I don’t want to be the feminine supportive neutral person that has to be in the movie. There can be joy in it, but it’s not very rewarding as an actor because you’re so limited in what you get to express, although most of the time you’re working to support a really terrific guy.”

As a two-time Academy Award nominee, McDonnell would like more challenging work.

“The Oscar nominations gave me a solid foothold. I feel comforted by that. People take me seriously. They’ll listen to me, and I feel at liberty to say exactly what I think.”

And she believes it’s time for more films such as “Passion Fish,” in which the story revolves around her.

Next up is a feature film, “Mariette in Ecstasy,” in which she plays the Mother Superior of a nun who claims to have had an experience with Christ.

McDonnell has also completed a TV pilot, “High Society,” playing a book publisher opposite Jean Smart as a Jackie Collins-type author.

McDonnell believes she finally has reached her prime.

“I started being in front of the camera rather late compared to a lot of other actresses,” she says, “so I never had the image of myself as an ingenue. Even when I was an ingenue, I wasn’t–you know what I’m saying. An ingenue is inoffensive on all fronts, always nice to look at and never threatening. I was always a threat.”