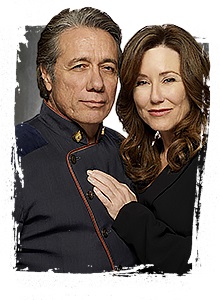

People’s Light brings McDonnell and Strathairn back together for ‘Cherry Orchard’

Tirdad Derakhshani

February 16, 2015

Ibsen brought them together in director Emily Mann’s 1986 production of A Doll’s House.

Nearly three decades later, Hollywood stars David Strathairn and Mary McDonnell once again will share a stage, albeit in less astringent material.

The duo, whose film collaborations include Sneakers andPassion Fish, arrived in the region last week for a new production of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard at People’s Light & Theatre in Malvern. The comedy-drama had its opening night on Saturday.

“We did a great deal together in the late ’80s and ’90s, and we always work well together, so there is this familiarity. But it has been a long time,” said McDonnell, 62. She’s best known for her Oscar-nominated role inDances with Wolves, and today she’s most visible as Los Angeles Police Capt. Sharon Raydor in TNT’s Major Crimes. Strathairn had his own Oscar-nominated turn as Edward R. Murrow in Good Night, and Good Luck.

They re-clicked again immediately. “I think when you know the person and you know their work and you come back together again even after many years,” McDonnell said, “you come back to a more trusting relationship and it really helps.”

Strathairn was more terse, if also poetic, about their reunion. “Mary! I gape and wonder,” he said of performing opposite her once again. “It’s a gift. It’s a gift.”

McDonnell, a Wilkes-Barre native who lived for some years in King of Prussia, hasn’t starred in a play for 18 years, but Strathairn has steadfastly continued his stage career, including a years-long association with Philadelphia theater. He starred in a People’s Light production of Nathan the Wise directed by Adams in 2009, and he led the cast in Václav Havel’s Leaving at the Wilma Theater a year later.

“There are more opportunities in film,” he said, “but my preference lies with the theater.”

Director Abigail Adams said she and Strathairn “have talked about doing Cherry Orchard together for some time now. A couple of years ago he talked about [casting] Mary in the play, since he had worked with her many times in the past.” McDonnell heard of People’s Light through producing director Zak Berkman, a childhood friend. “It’s been thrilling,” Adams said, “to line up such an amazing cast.”

McDonnell and Strathairn play Chekhov’s aristocratic siblings Lyubov Andreyevna Ranevskaya and Leonid Andreyevich Gayev. They will be joined by McDonnell’s daughter, Olivia Mell, as Ranevskaya’s daughter, Anya.

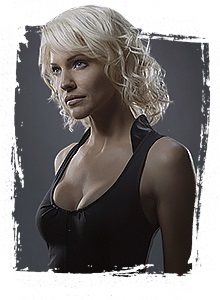

“It will be the first time we are acting together,” said McDonnell. She gave birth to Mell less than a year after acting in that 1986 production of A Doll’s House. She says she looks forward to working together with her daughter: “Obviously, I have seen her work all her life, but I have never entered her process with her and collaborated with her as a colleague.”

A 2009 Brandeis graduate, Mell is making her professional theater debut. She says her mother’s presence calms her. “She is an extraordinarily giving actor. There are things from our relationship as mother and daughter that definitely helped [us with] our roles,” she said.

Having your mother in a position to evaluate how you do your job doesn’t exactly sound like a picnic. “She is critical in the most loving way. And I of her,” said Mell, whose father, Randle Mell, also is an actor. She said she was born to the profession – “This was the only thing.”

Mell said Anya, her character in The Cherry Orchard, is perhaps the only truly optimistic person in the story, which is about the social, economic, and political crisis that befell Russia at the dawn of the 20th century. The play is set 50 years after Russia’s serfs were freed from bondage. Without their free labor, families that had centuries-old estates began losing money. “Anya,” Mell says, “is the daughter of a family that owns a great estate that’s in decay.”

To stay solvent, Ranevskaya has remortgaged her estate – including its renowned cherry orchard – several times. Now she’s in danger of losing it all.

Chekhov’s play presents us with various responses to the crisis. The siblings are befuddled by their situation. They’re told they must sell their orchard to pay their creditors or risk losing the whole estate.

“To their class, to do anything that isn’t considered doing it the old way is heretical,” said Pete Pryor, who plays Yermolai Lopakhin, born a serf on the estate but now a wealthy landowner. He’s a self-made man, a successful capitalist who counsels the impoverished aristocrats to sell the orchard. “The inevitability of foreclosure . . . and the idea that this is the only way to survive financially is something the [siblings] cannot understand.”

The siblings measure worth by sentiment, not money. They’ve never had to worry about their wealth. They love the orchard. Therefore, it is too valuable to lose.

While Lopakhin is the capitalist, Anya’s tutor, Petya Trofimov, is a socialist who advocates the redistribution of land and wealth.

With great wit and a touch of satire, The Cherry Orchard exposes the weaknesses inherent in each system. Unlike Tolstoy, who propounded a form of Christian socialism, Chekhov does not endorse any particular view.

“He did not have any real interest in politics,” said Adams. “For him, the artist’s job absolutely is not to have a message but to ask a question.”