Mary McDonnell Builds a Bridge Across Cultures

Peter M. Nichols

December 2, 1990

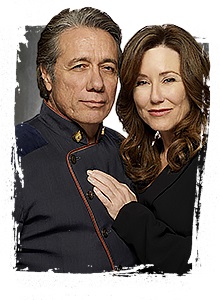

Mary McDonnell had played many kinds of women on stage and film — a boarding house proprietor, a lesbian feminist, a social worker, a beleaguered yuppie — but how would she perform as a white woman who had lived virtually all her life on the prairie with the Lakota Sioux? “I had to find my way into authentic territory,” Ms. McDonnell says. “I had to lose the New York actress and believe my way into the story and be this person in that situation.”

As Stands With a Fist in Kevin Costner’s new film “Dances With Wolves,” Ms. McDonnell has won high critical praise for a strong, sensitive performance as a woman raised since early childhood by the Sioux. In adulthood she is asked to cross back into white culture to help preserve the welfare of the tribe with which she lives. On a personal level Ms. McDonnell plays a character who lost one way of life and reached out to gain another. “I was struck by this woman,” she says. “What did she do with her life?”

As a tot named Christine, Stands With a Fist was living on the prairie when Indians massacred her parents and carried her off. As a woman, long since given her Sioux name and fully acculturated into the tribe, she falls in love with Lieut. John Dunbar (Mr. Costner), a cavalry officer who himself deserts white ways to live with the Sioux.

To converse with Dunbar and act as an interpreter for the Sioux, Stands With a Fist is asked to use a language she only dimly recalls. With that, of course, comes pain. “She carries this trauma inside her,” Ms. McDonnell says, “and she’s asked to go through it again in her memory, to regain her lost culture through the use of its language.”

In the film, Stands With a Fist, having long ago relinquished what she had as a white child to accept what was offered by the Sioux, again must deal with the pain of change and growth. “What we have is a serious person with tenderness at the core,” Ms. McDonnell says.

In her relationship with Dunbar, she finds her stability threatened as she is asked to remember and relive her loss. “She has to set up a duality,” Ms. McDonnell says. “As an adult she again has to let in that pain, face up to it and move forward with it. In the process, she wins love and intimacy. That’s an interesting lesson of a life well lived.”

Throughout her career Ms. McDonnell has played women in trying circumstances. As Shelly in Sam Shepard’s “Buried Child” (1978), she was a young woman used and emotionally banged about by those around her, but in several roles since she has played characters who grow in their powers of understanding and self-sufficiency. As Nora in a 1986 Hartford Stage Company production of Ibsen’s “Doll House,” she played an icon of feminism. “She fairly dances her transformation,” Mel Gussow wrote in The Times, “from playfulness to bewilderment to defiance.”

Ms. McDonnell, 37, is married to the actor Randle Mell; they have a 3-year-old daughter, Olivia. Raised in Ithaca, N.Y., she began acting as a college student at the State University of New York at Fredonia. Her stage work since has been regional theater and in New York. In 1988 she was Tom Berenger’s wife in Dennis McIntyre’s “National Anthems” at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven.

On Broadway she was one of several actresses who played the title role in Wendy Wasserstein’s “Heidi Chronicles.” Most recently, she performed in Darrah Cloud’s adaptation of Willa Cather’s “Oh Pioneers!” at the Huntington Theater in Boston, in a production scheduled to be aired on PBS’s American Playhouse next May.

On film, her most notable role before “Dances With Wolves” was as Elma Radnor, a boardinghouse owner, in John Sayles’s “Matewan” (1987), set during a labor dispute in the West Virginia coal fields in the 1930’s. “Elma was a bit like Stands With a Fist — two strong women connected to the soil — but Elma couldn’t contact her resources of joy,” Ms. McDonnell says. “That’s one difference between Stands With a Fist and the other women I’ve played. She emerges as a successful, positive woman on a personal level. The others were strong, but I’m not sure what their next step would be.”

Stands With a Fist rides off with Dunbar. “With her duality, she gains a completion. I feel she proceeds with a very full life.”

Much of the film’s dialogue is in Lakota Sioux. “The biggest difference with this role was learning and acting in another language,” Ms. McDonnell says.

On location in South Dakota she was tutored in Lakota for several hours a day. She was also given the time to gain a sense of place and relate it to her character. “I’d always flown over the prairie and seen this vast brown and green,” she says. “I didn’t understand the life there. Shooting started in July, but there was a month before I started my scenes so I had a lot of time to be with the people and absorb the environment. I was able to feel a little of what the child Christine experienced. Just waiting put me in the rhythm of what I had to do.”

In his Times review of “Dances With Wolves,” Vincent Canby writes of the film’s somewhat romanticized approach to the Sioux, with Mr. Costner embracing all things Indian with an enthusiasm that at times “teeters on the edge of Boys’ Life literature, that is, on the edge of earnest silliness.”

Ms. McDonnell thinks that everybody has certain expectations for a story that deals with history. “People need to relate in their own way, with the information they have,” she says. “I think the film stays inside a certain human rhythm and simplicity that allows it to be as powerful as it is.”