Battlestardom: Conversations with Mary McDonnell

Julie Levin Russo

March 2, 2007

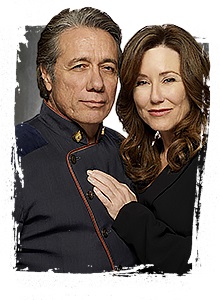

On March 2, 2007, Brown University had the honor of hosting Mary McDonnell, the acclaimed actress who portrays President Laura Roslin on Battlestar Galactica, at a panel discussion entitled “(Re)Producing Cult TV“. Following an introduction by Lynne Joyrich and short talks by Melanie Kohnen, Alanna Thain, David Bering-Porter, and Julie Levin Russo (which are reprinted, along with three other essays, in this issue), we opened the floor to Mary and to audience questions. Below is a reconstruction of core conversations and statements from the hour-long Q&A. The dialogue has been reorganized around sequential themes, and, because it is compiled from notes, all quotations here are approximate. Following this introductory recap, we are delighted to present the full text of a follow-up interview with Mary.

AUDIENCE

Mary opened by graciously acknowledging how thankful she was for the opportunity to be part of “a creative event that has stimulated this level of discourse.” She commented that you don’t realize, when taking on a role, quite the repercussions it may have and that it can be hard to relax into those responsibilities. “It takes a different part of the brain to analyze than to act,” she said, and she has to “move herself into that level of thinking.”

LAURA AND MARY

One attendee asked: “When we look at you, we see more Laura than Mary — how does that feel to you?”

Mary replied: “I like it!… I love being able to speak for Laura…. I don’t experience her as my creation…it feels good to facilitate her…. According to my family, it’s getting very blurry at home!”

Mary mused on the difficulty that she faces in reconciling her own beliefs with Laura Roslin’s tough choices. She finds that, in inhabiting Laura’s life, she often has to disengage from her feelings. For example, regarding her character’s decision to infect Cylon-kind with a deadly virus, she said: “I haven’t found a way to order a genocide with compassion…. You have to really figure out how to plant your feet and stand there and support genocide… as a person first, a woman second, a leader third, an actress last… if you feel it, it’s torture…. I’ve lost sleep over it, because it haunts me…. It’s very awkward, it’s very frustrating at times — but it’s also very real.”

While acknowledging that “this season [the third] has been a very difficult thing with Laura Roslin’s marginalization,” Mary nonetheless emphasized that she sees “strength in [Laura’s] writing in some very brief moments…. She has been reduced on one hand, and strengthened in another.” She also rationalized that “the producers are always a little afraid to box [Laura] in a corner before seeing where they’re headed with her… to leave her in that position of confusion seems to be where they’re comfortable.” For her, these limitations translate into part of the reality for her character, and she sees the two of them — Mary and Laura — as partners in a struggle on both of these registers to create more possibilities for women like Laura. She doesn’t want either of them to be cast as a victim. “[Laura] has her own existence and she’s trying to push her own image of power forward, and the writers are grappling with her.”

GENDER

From the audience, Stephanie Nicora noted that Battlestar Galactica is superficially feminist, with women in charge — but this seems to be true more of the Cylons than of humanity. In fact, Rousseau’s notion of separate spheres seems to be entrenched in the show: Roslin is President, but she can’t do anything much without the support of Galactica — headed by Commander Bill Adama, a man. When Admiral Helena Cain arrives, a female military leader, both Roslin and Adama agree that she’s a dire threat. Roslin doesn’t even have control over her own body — no one asks her whether or not she wants the cure from Hera’s blood — and by extension she is forced to adopt a pro-life stance and ban abortion. Her question: as a feminist, what’s your interpretation of these narratives?

In the ensuing discussion of the labyrinthine gender reversals and contradictions in play in the characterization of Laura and Bill, Mary observed that “they’ve given him all the feeling… I call him Adama-Mama, because he’s more emotionally involved with his son, the Cylons, the people.” Laura has by some measures become more extremist while Bill has become more moderate, and if, in fact, she inflects toward a more “feminine” role, then she must become more rigid in other ways to compensate. This is one rendition of the traditional duality (madonna / whore, loving mother / ruthless politician) that structures Laura. Mary described this as the problem of “how the feminine in nature finds a way to open itself without being killed,” and went on to say that “the human element of being divided into opposites…is very real to me. Sometimes I hate it, and sometimes I love it.” Ultimately, she’s aware that she’s negotiating with story-telling form a very male point of view, but her job is to facilitate what she’s been written.

Reacting to the ambiguity of Laura and Bill’s relationship, Mary was adamant that “a sexual involvement [is something that] Laura can’t even comprehend at this moment; no matter her emotional relationship, she can’t do it. She wouldn’t let it in, in order to keep her focus on her ultimate goal: getting these people to Earth.”

SEXUALITY

One audience member asked: “How is it possible that, given that it’s an amazing show on so many issues,Battlestar Galactica hasn’t had any gay characters?”

Regarding the show’s portrayal of gender, Mary had lamented that, “at the starting gate, there was a chance to blow it apart, and there was a retreat”; though she added that, “I state this all as part of a positive process.” This theme recurred when the issue of sexuality was broached. Speaking frankly about the climate in the writers’ room, Mary speculated that, as a group of primarily young straight men, “there isn’t necessarily a burning desire on [the writers’] parts to allow, particularly, lesbianism a full throttle on their show, because they are afraid.” That is, they tend to take baby steps toward novel and progressive perspectives and then get scared and pull back.

Another audience member said: “It’s outrageous to think of a woman as powerful as Laura tied to a man like Adama. As a lesbian myself…what we want for her character…”

Here Mary interrupted gleefully to affirm the sentiment: “I hear what you want — you want her to come out!” “Where are the goggles?” she joked, referring to the pink sunglasses (aka “girlslash goggles”) that speaker Julie Levin Russo used as a prop to illustrate queer reading strategies. In fact, Mary’s first action when she stepped up to the podium was to don the goggles, a dramatic gesture that made the crowd go wild. “So, I had no idea,” she said then, laughing. “I think I’m blushing.”

In response to the question, Mary referenced a TV Guide interview that was then on newsstands, wherein she had raised this same issue herself when she was asked: “What topic would you like to see the show address that it hasn’t explored yet?” At Brown, she paraphrased, “I would love to see us open up to the diversity of our sexuality as human beings.” (The actual published quote reads: “I know something that keeps being asked of Galactica is the sexuality issue. We haven’t really gone near that at all, and that would be kind of interesting. There’s so much to understand about procreation, sexuality.”) It was emphasized in the discussion, furthermore, that the heterosexual couples onscreen aren’t necessarily normative.

THEOLOGY

Religion is one of BSG‘s most fascinating and provocative themes; the alignments here are not what we’d expect. Mary believes that the show has the potential to “move, in a very targeted manner, toward an explosion of the Judeo-Christian paradigm,” but she conjectured that the producers backed off on Laura’s religious affiliations because they were concerned about appearing too right-wing in projecting our current administration’s fundamentalist beliefs (“I guess I can say that; this is Brown University,” she quipped). This constellation also intersects — albeit, very paradoxically — with gender and sexuality: the monotheistic (some might say religious extremist) Cylons are all for sexual exploration, while the polytheistic humans seem much more repressed, with narrower sexual norms. Moreover, the lapsed storyline of Laura as the Pythian prophet references the stereotype that women are more religious (i.e. “natural” and “irrational”) than men, though it’s worth noting that religion and spirituality are far from equivalent. This gendering holds even among the Cylons: Brother Cavil comes across as a mercenary sceptic despite his role as priest or guru, while it’s the female Cylons Six and Three who believe fervently in their God and divine destiny. Laura’s “feminine” faith and visions are threatening — literally so when she sparked a military coup (season two).

TECHNICITY

Like Battlestar Galactica‘s portrayal of religion and politics, its portrayal of technology — particularly as manifested in the “skin job” Cylons, who embody a racialized iteration termed “technicity” — pushes beyond a conventional opposition between positive and negative representations. This ambiguity may make viewers uncomfortable, but hopefully in ways that are thought-provoking and productive. Referring, in her talk, to the injection of Hera’s blood that cured Laura’s cancer, Alanna Thain commented that “Roslin herself could be considered part Cylon.” Mary shook her head and made a face. Yet she later underlined the import of Laura’s hybrid constitution, noting that Laura could be regarded as Hera’s daughter and Helo and Sharon’s granddaughter! She said that she hopes that following this connection will help the writers to loosen Laura from her gendered paradigm. Nonetheless, Mary maintained that Laura makes a lot of her choices through “fear of the other,” and thus her own perspective is “filtered through a purposeful ignorance. I don’t spend a lot of time contemplating Cylons; I just throw them out of airlocks!”

One attendee, citing the captions in BSG’s credits sequence, which explains the initial Cylon resurgence, asked: “What lies between ‘they rebelled’ and ‘they evolved’? Why decide to be human?”

Similarly questioning the human/Cylon boundary, and pursuant to the revelation of the “final five” (since, at the time of the Brown event, the season three finale, which outed four “sleeper” Cylons among the humans, had not yet aired), another member of the audience inquired: “as an actor, do you know if you are a Cylon? Have you gone and asked? Would that change your interpretation of the character?” Mary responded: “I would definitely ask for more money [laughter]. I have seen the final five [dramatic pause]. But I don’t know who they are. We have asked; they won’t tell. We sometimes beg them, because, as an actor, you make choices based on a narrative, [for instance] if you were going to be a toaster. We don’t know, [and] in truth it’s better — the limitations of ignorance are very human, unfortunately. We have to be innocent to this stuff.”

TRANSMEDIA

Mary echoed the enthusiasm and engagement of the audience when she suggested that we might move beyond the corporate paradigm of current television into something much broader, a “liberating possibility” latent in the media’s capacity for participation. She called Ron Moore “brilliant.” “We were all at his house drinking wine, and Moore asked me to be in a podcast and I sat in the corner and said, ‘No!’ because the idea of sitting there watching myself as people so far away were watching me at the same time blew my mind! [laughter] … Maybe it’s time for me to step up to the plate.” What she learned at the panel, she concluded, is that “the show needs another ten years.”

November 2007: Mary graciously called from the set of Battlestar Galactica in Vancouver to speak with Professor Lynne Joyrich and Julie Levin Russo in the offices of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University.

LJ: One of things that we wanted to start with was just what is different for you, if anything, about engaging with an academic forum and scholarly publication in talking about this, in contrast to participating in events that are more oriented to your cult audience and your fans and popular viewers. Not that we’re not also part of that.

MM: I understand what you’re saying. There is a difference. From my point of view, it’s context, in that when I’m talking to the fans who are not coming from an academic point of view, the questions have more to do with plot points and [the] experiences of the actors performing and things like that, which is also great to talk about. When in conversations with an academic audience, what you’re also doing, what you’re bringing as well is almost a sociologist’s look at the world of Battlestar and its implications on a social and political level, so that it becomes a broader questioning. [In fact, my sister Judith McDonnell is a Professor of Sociology and a fan of the program, and we often discuss it.] It’s more complex. It’s more thematic. And, therefore, I get to take a look at the show other than for its entertainment value or storylines; you know what I mean? So that’s what I’ve noticed, is that it just has a much more sociological feeling about the discussion.

LJ: [Laughter] Well, hopefully, you also find it interesting and fun.

MM: Oh, I do, I do. I mean, that is what I find really interesting and fun about it, other than the fact than that you’re delightful people.

LJ: Thank you so much.

MM: Part of what excited me about becoming an actor when I was in college, which is where I started, is that my brain woke up. I started to think about all aspects of life through the lens of the theater, whereas, prior to that, I’d be sitting in a chemistry class or a history class or a math class, and none of it really tied together in my brain as something that was very interesting to me. But when I had to start studying roles and worlds, something came together about history, politics, shifts in culture, psychology. And so to be able to go back out and have people who are looking at it that way and writing these extraordinary papers about it and have the opportunity to think along those terms: to me it’s like having, you know, the cherry on top of the sundae. It makes it all more interesting for me.

JR: That’s fantastic. And we also wanted to ask you, speaking of your position as an actor: it seems as if you’re put in a somewhat paradoxical or contradictory position where, because you’re the public face of this show or these texts, you’re put in the spotlight in terms of talking about them and speaking about what they mean. But behind the scenes, you may have much less control over the shape and the way they’re structured, so I was just wondering how you negotiated that.

MM: In the past, I would negotiate it — literally negotiate it — a lot more carefully according to a certain set of rules. I felt, “well, what I would like to really talk about is this, what I know the reality is is that, therefore, you know, I’ll talk a little bit about this and a little bit about that.” But as I get older and I’m in the profession longer, I’m starting to see that neither one has clear boundaries. In other words, things that I might say are the reality in an interview as I perceive the character: it’s putting that idea out in the world. Then, the next time I go to play her, because I said it out loud, we may have a different discussion on the set about how this may be written. So it sort of feels to me that it’s all part of the same evolution, because we have writers who evolve and are very, very open, and they become more so every year. I think that the feeling of two different realities is lessening; it’s getting a little more grey, and therefore to me, once again, more exciting. The character can’t be everything you want it to be because you’re not writing it — I would never want to write it — but you still have your point of view regardless of what you end up having to do, and sometimes your point of view may be her point of view even though what she says might be something else. So you can make the thing that she says fit into a sort of social or political obligation. But the person that the character is can incorporate and have within [her] energy at the moment all of the thoughts and ideas that you yourself have gathered out there in the field of Laura Roslin andBattlestar, you know. I don’t know if that makes any sense.

JR: It makes perfect sense. It’s really fascinating and I think a very insightful perspective. It’s like a textual network.

MM: It is. It absolutely is. And it seems even more so, the longer we do it. Experiencing it this season, as everybody becomes more and more trusting of each other and the story, it evolves in a way that’s being informed now by the story and the universe coming back at us. It’s kind of an interesting thing. It’s like somebody writes the story, and then you all gather around and bring the story to life, and then you send it out — I was going to say through film, but now it’s digital — and then the story is out there, and it comes around back and informs itself again.

JR: It fits with the theology of the show certainly — “All of this has happened before and all of it will happen again” — these temporal loops.

MM: Oh my gosh, that never occurred to me; that’s absolutely right. It is, and I think that the imprints, the idea of the imprints, where there’s a print and there’s an imprint and then there’s a reflection and then there’s another image that comes behind that, and then you find yourself — we find ourselves as actors sometimes, and this is an incredibly disciplined group of actors. This is not the kind of group of actors who can’t remember what they did in the last episode because we’re all disciplined storytellers. We bring our storyline, you know, every single episode. However, the accumulation of this sort of image out there in the world of Battlestar and its imprint has become its own thing, and sometimes you’re in the middle of something and you really can’t remember the past. The present has become so informed; it’s odd. You become very, very present with the now, and then you try to go back, and it’s almost like what really happens in life, which is [that] you really don’t always remember what happens. You just know who you are, and then the pieces of information that make you who you are are there, but you have to stop and think about them.

LJ: Well again, as a continuing TV story, it does have [that] growing memory.

JR: It’s one of the most wonderful things about television narrative.

LJ: So you mentioned the writers a moment ago, and this ties to an issue that had come up when you were here [speaking at Brown University], which is: it’s true that Battlestar is written by some amazing people, and that, in particular, they’ve really created some amazing female characters, probably because there are also some amazing female writers on the show. But you’ve also talked about how you still had some questions about the gender politics of the show or wish it could go in some other directions. So what are your thoughts about that?

MM: My feeling now is that the gender politics, or the experiences of gender in this role, have been utterly appropriate to the experience of the character in the world that she’s in. And that the writers and myself, who are the ones that negotiate her issues, have to a certain extent evolved together. And so what I’m experiencing, in retrospect, is that I learned through her evolution, through coming up against wanting it to be a certain way as a woman and having it go a different way because I wasn’t in control of the writing, [through] the experience of having the world around me not offer me the opportunity to be the kind of politician that I would like to be as a woman but to have to cope with the culture that’s coming at me which is not female. In the long run, I now feel like, if we could start this over, this story, and Laura Roslin had all this information, she would be able to maneuver through this particular political/social culture and maintain more of her desired agenda. [Laughter] It’s like, oh my god, we (she and I) have learned so much! [And we have excellent writers.] Because a lot of writing is at its best sometimes when it’s unconscious. And so, not intending anyone to go this way or that way, it evolves in such a way, and according to the energies of certain actors — you know, all the actors really — you find yourself in positions that you didn’t intend.

LJ: One of the things you mentioned when you were here was that you did sometimes wish that they wrote Laura more in relationships to other people. You talked about how there aren’t that many scenes with her and other women, or even with the male characters on the show. So, do you wish that, for instance, they [further] emphasized her friendships with other women, or even gave her a romance? Or is that the bind of women in power: they can’t be seen as both strong and sexual at the same time? [With] those kinds of things, would you want changes? Or no?

MM: Well, it isn’t so much that I would want changes; it’s that I can see the limitations of the culture as it exists in the writing. And certainly in the world of Battlestar, the duty to be performed, and the disease to be borne, and the ideas of isolating the female leader are very thematic there. As an actress, to play that is a very difficult thing at times because you can’t express who you are through relationships, given that she doesn’t have a relationship, a sexual relationship (we think…or maybe she does!). [Laughter] There certainly isn’t an expression of it in the writing; we don’t give it airtime, if it’s there at all. And so it does become difficult to have the opportunity to shape the full-bodied woman, because you’re only seeing her over and over again in specific [situations] instead. So sometimes that’s a little daunting, to find out how to be articulate within limited relationships with those around you. Whereas there’s lots of story about other people’s relationships, right? But as I have matured with her and played that fully, and played the limitation and played the isolation and watched what has evolved in her as a result of that and seen where they’re going now, I feel like it’s actually a good story, told this way. Because we get to see the example of a limited life.

Now, do I aspire toward that, and do I think that’s true for women in power? No; I think a lot of women have grown way beyond that. But I still do very much believe that women in power are threatening to the culture and that the culture continues to try to find ways to shape them and box them in. And I don’t think we’re beyond that. Can a woman be successful and overcome it? Absolutely. So I feel kind of mixed about it. To answer your question: on the one hand, I wish it was more [that Laura] had a fuller life, and we could see a full-bodied woman enjoying power and doing it well; on the other hand, there is something really gratifying about committing to the limitation. Because it is out there, and we do have to fight against it. I mean, it seems somewhat real to me, the more I play it. There are obviously very successful women in power, who have full lives, clearly. But I’m not sure that the prejudice is not right around the corner. And I’m not sure that these women haven’t had to continually try to overcome it.

JR: I think those limitations are all still there, even if people manage to find their way within them.

MM: Oh absolutely. I think we’re trying as a culture to move beyond it, but clearly, if you just look at what’s going on in the Democratic Party right now, we are definitely burdened still by these ideas. They’re projected all over the place…like giant projectiles.

JR: And another place where it seems some of these double binds come up is around motherhood, which is a theme we talked about when you were at Brown. So I’m just wondering what your wishes are for the way the dynamic of motherhood, both metaphorical and, by some measures, literal around Laura is going to play out, given how it’s such an ambivalent position for women.

LJ: Right, she’s sort of the mother of all the humans but then also has this particular relationship to this one child. And again it seems like, as Julie said, that double bind about a woman in power, [together] with these maternal qualities that are often seen in our culture as stereotypes, make those in contradiction. So, [what is] your sense of how that’s playing out, or what you would want for it?

MM: Well, to talk about what I want for it sort of no longer applies. [Laughter] And I don’t really mean that negatively. I just think it’s turned into such an astonishing role to play. But you know there are so many things I can’t really talk about without it being spoiler-ish.

JR: You can spoil us, we don’t mind!

MM: No, I can’t spoil you; I’ll get in so much trouble! My experience is that it’s very difficult to talk about that aspect of things without revealing more than I am able to at this point. But what I can say is that feminine responsibility, the responsibility that women feel towards survival and towards the betterment of humanity, is a very strong force in Laura. She may not identify it, and certainly doesn’t speak about it, because she doesn’t ever really have an opportunity to indulge herself or anyone else in what she actually thinks or feels. But she carries with her something I think that women carry, which is that we feel responsible for life, for human life. And that journey for Laura, and the experience of that responsibility for life, only grows deeper and gets more complicated in this saga.

LJ: Interesting, very interesting.

JR: I’m trying not to squeak because I’m so excited!

MM: No, it’s really — by the way, the whole thing that we’re shooting right now is so unbelievably…it’s not quite like anything I’ve ever experienced.

LJ: Oh, wow. You’re really whetting our appetite.

MM: It’s going to be great. Great and overwhelming, really. We are very, very under lock and key right now, more so than ever before, so I have to be careful. But I will say just sort of thematically, that being in the middle of the end, right? Which is kind of where we are — and then suddenly we’re going on a writer’s strike, so we’re being stalled. We’re all sort of looking at each other, and it became apparent to me a couple of nights ago that one of the reasons this is seeming to be so difficult to do at the moment is because it’s becoming a clearer and clearer and clearer reflection of the horror of life as it is occurring right now all around the world. That [with] the complexity of the dissolution, or the dissolving, or the disillusionment with our old ways of thinking, watching it is like turning on the news. It’s sort of like watching the world dissolve around you. And what that means for the feminine or the female experience: perceiving that is kind of an agony. So I think it continues to be, for Laura Roslin, an experience in under-expressed feminism or femininity, but deeply felt. And isn’t that the plight of women? I mean, not you guys. [Laughter] Not you gals. But women, you know what I mean, out there? They’re still not speaking. Anyway, don’t get me started on women.

LJ: I don’t know if you can answer this, but what you were just saying also seems like it ties into a lot of the religious aspects of the show, or the theological issues that the show brings up.

JR: We could extrapolate that, now that Laura’s cancer is back, it may also prompt a return to the Pythian prophecy storyline and that Laura’s theological status may again come to the fore. I know we talked in the past about some of the (gendered and political) troubling implications of that.

LJ: But also, [as] you were just suggesting, maybe the potential in that [is] the spiritual linking of ideas of life and feeling responsible for life. So, I don’t know if you had any thoughts about that you wanted to share.

MM: Well, I would love to, but I can’t.

LJ: Maybe in general, if you can’t tell us about the upcoming plot, do you have any thoughts about the way this show engages with those questions of religion and spirituality and theology? Which I actually think is quite rare for TV. I mean, a lot of television programs seem to deal with that, but in quite a simplistic way, and I think one of the things that’s amazing about Battlestar, as you were just getting at, is that it deals with issues of politics in a very complex way, issues of history, issues of gender, but [it also ties these] not only [to] political questions, but [to] people thinking about spiritual questions. So even if it’s not framed in terms of what will happen on the show, if you had any thoughts about just the fact that the show deals with that at all?

MM: Well, I agree with you in that I think Battlestar is unique in television. You have a television show over here and it will be dealing with politics or war or religion, and you’ll have a storyline that will talk about those issues. And people in the story are behaving in a way that’s familiar to us because we see it on the news, and we see it on entertainment news, and we read about it, and we go, “Those people are behaving [in the way they were behaving in] that story that I saw the other night. They’re talking about the same thing.” What Battlestar seems to always do, which is what it did for me in the miniseries — and [what] it continues to do, even as the issues get deeper and more complex and more bottom-line — is Battlestar brings up a question of how we perceive the issue that we’re in the middle of. So that we’re constantly being asked, as characters, [to] question ourselves and the perception and reality, rather than just playing out the issues in the dramatic form.

I just leapt from being a character to an actor really quickly. So there’s two different things: in a normal television show, the actors might be asking those questions but then playing the characters who are just playing the dilemma. In Battlestar, the characters are also playing the dilemma and questioning the dilemma simultaneously, because there is multi-leveled reality that is influencing how they are perceiving any given situation. So the beauty of that for me is that Ron Moore — and I do believe that it constantly really does come from that man — has a quest to understand perception. And out of his need to understand life as we perceive it or life as it exists (or are they the same?) comes these stories that replicate stories that are happening to us in life, but they’re infused with a wiser way of going at them. Because we’re bringing along belief and perception, belief as opposed to perception. Is faith something that you have, or is faith a belief that’s prescribed? What is faith, what is faith in God? Is that a dogmatic idea that seems to suit you, or is faith in God something that has to do with reality as you understand it? Can you be God? You know what I mean? So I think he allows this world, allows us a much more honest experience of how uncontrollable reality actually is. How beyond our control it actually is, if we want to actually sit in the moment; it doesn’t have the safety and control and the limitations that we would like to give it because it’s easier to see it in that way.

JR: I just wanted to comment that I think that incredible complexity and philosophical self-awareness, or self-reflexivity, in the show is a lot of what has gained it such a large and passionate following among academics. I mean, it has made a sensation within intellectual circles.

LJ: And like you were saying, the show is so complex because it’s layering all the issues together — politics, history, gender, spirituality. And it’s also showing debates among the different people or the different groups on the show about those things, so that it’s not just one version being played out: the Cylons have one way of thinking about things, the humans have another, [but] even within those, it’s much more complicated. Can we ask about — again, I don’t know how much you can say — either the further distinguishing between humans and Cylons or the further merging between them?

JR: Or, can I just add — and I think this is very much in this vein — I know in the past you’ve expressed some distaste at speculation about Laura being a Cylon, and I’m just wondering, within this world of complexity: What’s so bad about being a Cylon, and have you and/or Laura been forced to shift your position on this?

MM: Totally [from] her point of view, what would be so bad about being a Cylon would be that it would completely shake the foundation of what Laura believes she is even alive for. In other words, she should have died a long time ago, according to the pilot. But, instead, everyone else died, and she became President. And Laura has held a belief in [the] job [she must do], and so the idea of being a Cylon would threaten that so unbelievably that she can’t let it in as an idea, because she doesn’t know how to proceed…or perceives that she wouldn’t know how to proceed. However, for the actress, the challenge, then, is being able to see the world more clearly than your character can and being brave enough to be blinded…because you want to know everything so that your character comes out on top. [Laughter] You want to sort of have, “But I think she… I would be that smart, I would know that if I could blend myself, that peace would reign,” blah, blah. But you can’t, because that’s not your job. So the tricky part is asking Mary what would be so bad about being a Cylon, and she’d be like, “Well, hey, let’s go, because then I could carry both of those things in me and help deepen the fact.” My belief is — Mary’s belief is — that we’re all the same anyway.

LJ: Right, because the show really does question what even counts as life, what counts as human.

MM: That’s right!

LJ: What’s our relationship to technology — is that a totally separate thing, or are we all technological in a way and, at the same time, all human? What’s the value of human life? From the stories that they’ve done, that you’ve done, about torture to the stories about Cylons and technological beings, [Battlestar] really raises these questions about the status of life and how it should be valued and treated in a way that really complicates all that.

MM: And so the bottom line is that my character and several of us “humans,” quote unquote, on Battlestar: we have to root our perception of ourselves and our behavior in the emotion of fear. Because that’s what’s limiting our progress everywhere, right? Whether we’re Cylon or human, that thing that limits the wisdom and the progression of life anywhere is fear. So we have to root our experience in fear and protectiveness. That point of view is what creates these super-armies and anti-ballistic missile systems; you know what I mean? We’re afraid that somebody’s going to take something away from us that we own. And so you’re operating on holding on and being afraid, and so you defend — as well as protect, but your protection is defensive. So how does the human being evolve beyond fear? And, in terms of Battlestar, are the Cylons really that fearless? The humanity seems to be pretty apparent in both factions. The vulnerability to fear seems to be pretty apparent. So if there’s anything that’s tying them together, just in a general sense, it’s that the element of fear. In a perfect universe, if we could get beyond fear, wouldn’t things start operating on such a phenomenal level?

JR: This is, perhaps perversely, bringing me in mind of the writers’ strike. I think a lot of the human relationship to technology on the show seems to be so driven by fear because the Cylon intimacy and interdependence with technology is such a threat to what they at least started out as seeing as their humanity. And it seems that the writers’ strike is so much about the struggle between these much more retro media models coming out of broadcast and then these new formations that are happening around the internet. It’s just an interesting parallel struggle. [Since compensation for content produced for or distributed via “new media” is the central issue of the strike, the Guild and their allies could be seen to challenge our definition of what “television” is, and how we relate to it as techno-subjects, much like the Cylons challenge our definition of what “humanity” is.]

MM: It’s absolutely fascinating, and you’re absolutely right. We were talking the other day on the set — because we shut down in about five days. We only have five days of material left, and then we all go home and wait, right? And we are striking; we back the writers a hundred per cent. And the question is: are we going home for a few weeks, or are we going home for a year? Because, on some level, this is the reformation of the entertainment industry, and how long that may take — or will we go all the way…? Where are we going to go with it? Are we truly going to reform the entire system because it has outgrown the old modality, or are we going to get a little bit of a compromise and then everybody go back to work because the idea of reform at this time in the economy and this time in the state of the world is so frightening to everyone? And will there be a visionary person on either side of the issues that can create the new way for technology and artistry to evolve forward?

JR: Is Hollywood going to find Earth?

MM: [Laughter] Is Hollywood going to find Earth! And, when they get there, will it look good?

JR: And are they going to get there and then destroy Earth, or are they going get there and have a peaceful utopia?

MM: Are you going to give them Earth? Are you going to give Hollywood Earth? What will they do with Earth? It’s once again a very interesting parallel. It’s now; this is what’s going on. Hollywood is just a little tiny example of how humanity does not really understand who it is in relation to technology, and a lot of humanity is being usurped by technology. And some other aspects of humanity are crying out to slow things down, to re-examine what it means — the children of today, their greatest social context is the internet.

JR: They’re totally Cylons.

MM: I mean they’re online instant messaging or Facebooking, or whatever, more than they are interacting [physically]. And that is just astonishing to me, coming from a generation that—I remember the big deal. I remember taking my bath and putting on my best little PJs and slippers and bathrobe and jumping into the nice, upholstered chair with my older sisters who were twins, and the three of us getting ready to watch Peter Pan on television. Because it was a major broadcast event.

LJ: A very different model of viewing. And it’s true, the way that the audience has fragmented into different narrowcast groups. And people watch on the internet now.

MM: This is just a constant interaction.

LJ: Speaking of the internet, I was going to ask: do you ever look at those things? What are your feelings about the fan community on the internet?

MM: Well, first of all, I do think it’s very exciting. I do think it’s a very exciting world that gets stimulated and then articulated, and it’s like when you throw a stone in the water and the ripple, ripple, ripple. But as an actress, I find that the most potent way to play a character is to play [her] with as little exterior information as possible, once you know who you are. So in order to not rob you all, the fans really, of Laura Roslin’s personal, simple experience, I have to stay away from all of the exciting ideas that come up and all the discussion and all of that. I think it would be something [that] I would love to go back and take a look at when I’m finished playing her. It would be really fun to go, oh my God, this was all going on! And then I’ll probably go, oh, I should’ve known about this; that would’ve been a good idea! I’m sure I’ll regret all of it!

LJ: As I’m sure you’ve heard, one of the things that a lot of fan fiction tends to explore are questions of sexuality that are not fully elaborated within the program itself. And, again as I’m sure you know, many viewers have called upon the producers to do more with sexuality and to include gay or lesbian characters more explicitly, etc. And we have all heard that in…well, we don’t have to talk specifically about what happens in Razor, but, to connect it with what we had been saying before is, again, there had been this request on the part of producers for more gay or lesbian inclusion.

MM: And it seems like they complied!

LJ: Exactly, but in ways that some people, I think, will think…well, I think there’s going to be debate about it.

MM: How will the debate be? Like in what way?

LJ: I don’t personally believe this, but I think that some people will say it plays into the evil lesbian [stereotype], where the lesbian characters either have to be sneaky and evil or else die. One or the other.

JR: Or both, in this case.

LJ: I actually think, as with everything with Battlestar, what it does with it is much more complex.

JR: I think that’s one major criticism that’s out there, and the other major criticism is that it’s subtle.

MM: That it is subtle?

LJ: Some people think it’s too subtle.

JR: Which is seen as a cop out. Now I don’t personally agree with any of those, but those are the two major strands of criticism that are out there. But it’s just a sign of all the double binds of representation: that there isn’t really a way to represent homosexuality on television that’s uniformly visible. There are always going to be ways in which it’s visible, axes where it’s visible, and then axes where it’s invisible.

LJ: And then people put very big demands on any one representation, because again there’s not a huge diversity of representations of queer folks on TV, and therefore, with each one that comes out, it’s like people want that one to be the perfect one. As opposed to this [is] one character; it’s not supposed to stand for all lesbians. But in a situation where there aren’t a ton of representations to choose [from], I think that people pin all their hopes on [one]. But I don’t know if you had any further thoughts about gay representation…

MM: I do, I do. You know, without having seen Razor, but having read Razor, I certainly do know what we’re talking about here. And, to me, what’s interesting is that, once again, Battlestar brings up discussion and debate about the feminine and how women are portrayed in whatever circumstance they are in. And, once again, I’m reminded that Battlestar is a very male world searching for its femininity.

JR: And Razor is a real anomaly in that sense: it’s incredibly female-driven, and driven by relationships between women. Just to say my comment about Razor: which is that, in line with what we talked about at Brown, the most delightful aspect of it, for me, was that it provided this almost pedagogical example of the “girlslash goggles.” When you watch the dinner party scene, the way that it’s edited gives you this amazing demo breakdown of how to watch for lesbian subtext. And then it’s only retroactively that there’s a conversation where they acknowledge explicitly that that’s what was going on. So I just wanted to ask you whether trying on the girlslash goggles has changed your view of the show in any way.

MM: I didn’t have them on long enough. [Laughter] I should wear them around for a while, you know what I mean?

LJ: But that one moment you had them on was a good moment, right Mary?

MM: It was a really good moment! [Laughter] Once again, as an actress, I try to take as little exterior view of the whole show as I can. If I were producing the show, directing the show, or writing the show, I would put myself in a different position. As an actress, I almost know at times less about what you can see on the show than you know. But underneath it, the innocence of that is where the implications begin.

JR: Well, in some ways I think you’re giving yourself too little credit, because you speak with incredible insight and intelligence about the big picture of the show.

MM: Well, thank you; I appreciate that. But part of the reason I like to communicate about the show is because I don’t get too involved in an exterior view. I really am talking about, most of the time, what I read and what I think that may imply, what I’ve seen in final cuts (because, boy, is it different than what we shoot) and what I sense underneath, what I really think is happening. And talking with you all is different. For example, I learned a great deal just coming to your event. It’s like, oh my God! Like, oh yes, I do believe or feel or understand the show from that point of view; it’s just I don’t spend a lot of time talking about it. And because I don’t blog, I don’t watch, I don’t participate in chat-rooms — I don’t do any of that stuff, [so] I don’t get into these discussions a lot.

LJ: Well again, when you’re in them you say amazing things. So we really thank you (and I know that we’ve gone an hour now).

JR: I just wanted to say, in conclusion, this conversation came full circle, because we ended up talking about the same kind of multivalent textual networks.

LJ: We don’t want to be keeping you, because we’re so appreciative you’ve given us this amount of time…[but] I don’t know if you had any final thing you want to say or, if not, we can end.

MM: I just want to say thank you. I mean, I really, really, really appreciate the level of intelligence that Brown University and all that it’s connected to is bringing to the show. I mean, I think it’s a wonderful event that can continue even when [the series has been completed]. The implications of the show are going to go on for a long time. I was thinking the other day that it’s going to be very, very fascinating when the show is done, and there’s a complete saga to be viewed and understood, then [to] pull out and understand it as a complete story. And then there [are] even more and more conversations to be had, and then I can talk freely about anything because I’m no longer under contract!

LJ: It will be really interesting. Well, again, thank you so, so much for your time and for all of this, and we would love to see you again in person one day if that’s ever possible.

MM: It would be great.

LJ: And good luck with everything with the show!

Acknowledgements:

We’d like to thank David Udris for his invaluable technical assistance; Angela Fraga, Dana Rae, Becka Saalbach, Erika Villani, and Stephanie Yang for volunteering to transcribe the interview; and attendees and the Brown Daily Herald for their reports on the event.

Mary McDonnell Bio:

Mary McDonnell, who plays the lead role of President Laura Roslin on Battlestar Galactica, is an acclaimed actress working in theater, film, and television. Having performing for many years with the Long Wharf Theatre Company in Connecticut, she won a prestigious OBIE award in 1980 for her work in the play Still Life. On Broadway, she has performed in productions of Execution of Justice, The Heidi Chronicles, and Summer and Smoke. In 1991, her Academy- and Golden Globe- nominated supporting role as “Stands with a Fist” in the film Dances with Wolvesbrought her to international attention, and she was singled out again in 1992 with Oscar and Golden Globe nominations as best lead actress for her role in Passion Fish. Among her other films are Matewan (1987) Grand Canyon (1991), Sneakers (1992), Independence Day (1996), You Can Thank Me Later (1998), Mumford (1999),Donnie Darko (2001), and Nola (2003). She has similarly had a dynamic and varied career in television, even before joining the cast of Battlestar Galactica, starting in 1980 with a regular role on the soap opera As the World Turns. In 1984, she starred on CBS’s short-lived medical sitcom E/R, and later, in 2001, she guest-starred on the NBC drama ER , for which she received an Emmy nomination. She has also appeared in the 1995 CBS series High Society, in guest roles for other TV programs (such as Touched by an Angel), and in several TV movies or theatrical adaptations (such as, among others, PBS’s O Pioneers, TNT’s The American Clock, Lifetime’s Two Small Voices, Showtime’s 12 Angry Men, CBS’s Behind the Mask and The Locket, and HBO’s Mrs. Harris).